RAMONE ROMERO | Contributor From Japan

Recently I’ve been reading some discussions written by progressive Adventists. Their comments cover much doctrinal territory, and I confess it’s becoming difficult for me to read these exchanges. I am increasingly perceiving these comments to be these progressives’ attempts to invent their own definition of Adventism. That attempt may bring some peace to them, but what is the reality of “Adventism”?

The Gospel is a very simple thing: Christ has saved us. So in the midst of all these progressive discussions of Adventism, I’ve found that my heart wants to cut straight to the meat and ask, “What about the Gospel?”

The difficulty every progressive Adventist faces is the attempt to harmonize the gospel with historic Adventism—the foundation of Adventist identity. Although many progressive Adventists do not believe and do not actively teach the “old things”, in order to remain Adventists they must carry these “old things” along, giving them a place and some occasional but firm assent.

The Japanese family altar

Why would they hang onto old teachings even when they no longer believe them? I’ve found this phenomenon eerily similar to the Japanese tradition of keeping a butsudan in the house. A butsudan is a large, highly-decorated family altar to one’s ancestors (with a Buddha in the center). It gets passed down to the eldest in the family, and the eldest has to take it. If he/she does not, the refusal would amount to dishonoring the ancestors, and the rest of the family would be very upset.

The question of the altar has been an issue in church families in Japan; once a person becomes Christian, what does he/she do with the butsudan? Some have kept it quietly, and others have thrown theirs away (often we hear testimonies of spiritual lightness and/or healing which come right after throwing away a family butsudan). From a Biblical perspective, having a giant physical altar to Buddha and one’s ancestors in one’s home is an incredibly clear issue. Yet the nature of the territorial spirit in Japan obscures and confuses such otherwise obvious things. Sadly, many Christian families keep their family altars and attempt to harmonize them with the true God. Many claim not to believe in what the butsudan represents. There are even some who do not care for the altar, neglect it, or keep it closed in some corner of the house. But the one thing they do not do is throw it out. It must be kept.

I find it significant that no matter how “progressive” one becomes within Adventism, in order to stay Adventist, one has to keep the early Adventist things somewhere “in the house”, just like a Japanese family needs to keep the family butsudan to avoid offending the family or being cut off. The Adventist foundational beliefs demand the same reverenced position in the “house of God”. One may disagree with them and neglect them, just as progressives do. But to call them into question and suggest throwing them out produces the same effect in the Adventist “family” that throwing out the butsudan produces in the Japanese family: the family gets highly upset and a person can find himself or herself ostracized.

Doing the unthinkable

By the time a butsudan is passed down to the eldest in a family, often there aren’t many older family members left living to get upset. Yet still it is nearly unthinkable to throw the altar away. The reason behind this reverence for the butsudan is the deeply embedded belief within the Japanese culture that one’s ancestors continue on after death, and the butsudan is the place to honor them. Understood at this deeper level, a butsudan becomes much more than an idol, altar, or family heirloom; after the people are gone, it is the representation of one’s family. To throw out the butsudan is to throw out, insult, and disown one’s family.

In the same way, the Adventist “identity” cannot seem to exist without its historical foundation—the beliefs, writings, and claims of the early Adventists to a unique calling, message, and special truth. The Adventist identity is tied to these things like a Japanese family to a butsudan. The “unique messages” of Adventism become what define it. Adventists can’t let them go completely. If they do, they lose their identity.

…Adventists take it theologically for granted that the Holy Spirit is the founding and guiding spirit of Adventism’s heritage. To suggest that the Holy Spirit might not have been the founder of Adventism is like telling traditional Japanese that their ancestors are actually not still existing as disembodied spirits—neither group would be able to believe anything other than what they’ve always believed.

So just like the butsudan, the Adventist heritage “altar” is passed down from one generation to the next. Just as Japanese take it theologically for granted that their ancestors continue to exist in it as spirits, Adventists take it theologically for granted that the Holy Spirit is the founding and guiding spirit of Adventism’s heritage. To suggest that the Holy Spirit might not have been the founder of Adventism is like telling traditional Japanese that their ancestors are actually not still existing as disembodied spirits—neither group would be able to believe anything other than what they’ve always believed.

Keeping it quietly

For a Japanese family to become Christian and completely sever ties with demonic powers and strongholds, it means throwing out the butsudan, risking the anger of the living family, and letting go of a comforting belief they’ve always had. These potential losses explain why many Japanese Christians quietly keep their butsudans. They may want to continue honoring their family, or they may think the altar is merely “cultural” and not “religious”. They don’t notice that for one reason or another, they are unable to throw away the altar—it has a power over them. Many Christian pastors and members see no problem with keeping a butsudan and perhaps can cite theological rationalizations to explain such a decision. But these rationalizations are rooted in the desire to harmonize with the culture and avoid offending people by taking the Bible too literally. (Interestingly, my wife informed me that the “no problem” view of keeping a butsudan is very common among members in Japanese Seventh-day Adventism, even among “conservative” Adventists.)

Similarly, most liberal and progressive Adventist churches “quietly keep the altar” of Adventism.

As I talked about these things with my wife, she commented on the typical Japanese attitude toward a butsudan: “We just don’t have the idea of getting rid of it,” my wife said. “Leaving it closed, putting it away somewhere, or even replacing it is okay, but not getting rid of it.” As she spoke, my wife suddenly remembered than when she took Adventist baptismal classes, the pastor pulled out a large blue book. He explained many things from it about the “sanctuary”, few of which my wife understood. Before that moment, she had never heard of those things (and afterward seldom heard them again, except from American missionaries). Those foundational Adventist beliefs can be neglected like a butsudan, but on special occasions they are brought out.

Interestingly, she said that it is acceptable to replace the butsudan. This practice parallels the way many reform-minded and progressive Adventists update the old beliefs. The old beliefs, they think, are outdated and irrelevant. It is completely permissible to re-interpret or alter them to an extent, but like a butsudan, it is unthinkable to throw them completely away.

A new identity

Throwing out the altar—whether one is a cultural Japanese or an Adventist—means truly starting over. It means letting go of one’s old identity, even if one’s family becomes upset. One finds a new identity, however—child of God. This new identity is not defined by ancestors nor forefathers, nor is it defined by who we are. Rather, our identities are defined by who Christ is. Through the cross, He received our sins and punishment, and we receive His name and inheritance. Through the cross, His inheritance and position before His Father become our inheritance and position before our Father. His perfect life becomes our heritage. We find Him—instead of our religion—to be the unique and special One.

Room for the Gospel

In Adventist churches where the “old things” are not taught, the gospel is given more room to breathe. Where more of the “old things” are taught, the gospel of God’s grace is given less room to breathe The inversion is proportional. The further we move away from the family altar, the better. Why not let it completely go? Adventists fear the backlash they might receive from their spiritual family if they throw out the family altar. Further, the writings and beliefs of early Adventism are kept on the altar, so to speak, in a sacred place, and one’s identity is tied to them.

I do understand and sympathize with progressive Adventists’ reactions when they discover the truth about the things that formed Adventism in the beginning—”This is not my Adventism!” When they go outside areas such as Southern California or travel to less industrialized countries and see Adventist “evangelism”, they see something that challenges their understanding of their church. It reminds me of the story of Kang Chol-Hwan.1

Kang spent the first half of his youth growing up in relative luxury with his family in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. During that time, if some North Korean defector had somehow come to his family and told him of the harsh conditions, famine, and thousands of political prisoners kept in concentration camps, Kang and his family would likely have thought the defector was just consumed with bitterness and blind hatred. However, Kang’s comfortable life and beliefs about his country were forever changed when he was nine years old, when he and his whole family were taken away and imprisoned in the Yodok concentration camp. After being released ten years later, he escaped to South Korea and there attended university. Shockingly, Kang encountered people at university who did not believe what he told them about the North. Because most people there had grown up without the difficulties faced in the North, some of them did not believe that Kang was telling the truth. They thought he was just bitter and that his was a rare experience. They told him to keep his comments to himself and stop making trouble.

I understand that progressives may have embraced a “nicer” Adventism, a healthier theology with less extremism than that which frequently characterizes historic Adventism. They may have settled in more Gospel-friendly areas. Their experience represents “Adventism” to them. Yet for others, Adventism has been North Korea (figuratively speaking). Which is the “true” Adventism?

When looking at the historical literature and events of the founding of Adventism, we discover why the awareness of the Gospel decreases or increases in proportion to how much the “old things” are taught or left untaught; foundational Adventism was clearly gospel-hostile.

Adventism compared to Buddhist altar

How dare I compare the early Adventist beliefs to a Buddhist ancestral altar? I do so by simply comparing the gospel—even as progressive Adventists know it—with the early beliefs of Adventism. The central truth of the gospel of God’s grace (justification by faith) was missing for the first forty years of Adventism—the time in which all of Adventism’s “unique truths” were completely formed. The early Adventists’ “good news” consisted of knowing the scripturally unsound “shut door” and Sanctuary teachings. As the “shut door” theory evaporated because Jesus did not return, the core doctrines expanded to include the keeping of the law correctly (particularly the seventh-day Sabbath). If a person disagreed with these core beliefs and became a non-Adventist Christian, that person was considered “apostate”, a member of “Babylon” and the “fallen churches”. He or she was worshiping “Satan impersonating Christ.” Such beliefs and teachings as these were given divine credentials because they were supported by Ellen White’s visions and instructions from supposed angel guides or Jesus Himself.

To summarize: 1. The gospel was missing from the first 40+ years of Adventism. 2. Anti-gospel beliefs were confirmed by a “prophet” who had visions and received instruction from “angel guides”. 3. The “angel”, the “prophet,” and the early Adventist teachings condemned those who clung to the gospel instead of to the new Adventist teachings.2

This reality adds up to the working of a spirit other than the Holy Spirit. Imagine you had a friend today who did not know the gospel, who received new “truths” from “angels” that contradicted the gospel, and condemned people who clung to the gospel instead of the new “truths”. Wouldn’t you pray for your friend’s deliverance? If you had a Marian-Catholic friend who prayed to Mary and received “answers” from her, wouldn’t you want your friend to be delivered from the false spirit and its teachings?

…it is no wonder that Adventists have trouble envisioning their identity in Christ apart from the “unique” heritage of Adventist beliefs. It is not enough to embrace a partial teaching of Christ’s righteousness while keeping a different altar in the house — because the altar isn’t empty. It still holds a power over the household, and the family cannot throw it away.

Keeping a butsudan—a Buddhist ancestral altar—in the house cannot fail to have an effect on a Japanese family. For example, many children and adults are choked at night by spirits and cannot move. In the same way, keeping the 40+ years of teachings from an anti-Gospel spirit (that deceived our forefathers) in the Adventist “house” cannot be without effect—it chokes the gospel and the lives of Adventism’s children and adults. It is no wonder that there is such confusion about the gospel when people read the old literature. It is no wonder that progressives who disagree with the old things still have difficulty clearly saying the early things were simply wrong. Likewise, it is no wonder that Adventists have trouble envisioning their identity in Christ apart from the “unique” heritage of Adventist beliefs. It is not enough to embrace a partial teaching of Christ’s righteousness while keeping a different altar in the house — because the altar isn’t empty. It still holds a power over the household, and the family cannot throw it away.

What kind of reform is needed?

Adventists can attempt to reform their modern churches and teach people how to read the “Spirit of prophecy” with one eye closed—re-interpreting it, taking the “good” and leaving the “bad”. It can try to grow “Southern California-styled” progressive communities throughout the Adventist world.

The problem, however, is that the fruits of historical Adventism—misunderstanding or distortion of the gospel, fear of the end times, cultic separation from other Christians, insecurity about one’s salvation, cognitive dissonance, the anxious pursuit of health and success—these things continue popping up like sucker shoots from the grafted root of a plant no matter how progressive the Adventist community tries to become. No matter how much “gospel” is grafted onto the root of Adventism, the bad fruits can still be produced because the old root remains intact. The gospel-hostile spirit of early Adventism is able to re-emerge simply because the family has kept an altar for it in the house and staked its identity on it, like a butsudan in a sacred place.

Just as some Japanese families attempt to hold onto both a butsudan and Christianity, trying to keep both identities, so many progressives may be trying to hold onto both the Adventist foundation and Christianity (perhaps calling this syncretism “diversity”). Their attempts to reform Adventism continually fall short because the family “altar” is left in place. Deep inside, even the most progressive Adventists know that the institution as a whole is still attached to its foundational beliefs which are written into the church’s doctrines, manuals and textbooks. The butsudan demands a place and must be given it, even in progressive churches. It does not want to be removed.

The reform desperately needed is the one that looks the most painful at first: each of us must let the gospel break us apart and re-form us from our foundation. By letting go of the family altar, Adventists can discover their heritage solely in Christ and in the family of God.

The Adventists who risk this reform would tell a story of transformation: “I once was lost, but now am found; I was blind, but now I see.” Progressive Adventists can become even more truly “progressive” by continuing to “progress” away from the gospel-hostile spirit that shaped the beliefs of the denomination for more than 40 years. Many can easily disagree with the “old things”, but few are able to think of throwing out the altar. Though privately disagreeing with early Adventism, few progressives are able to say that Adventism “was once blind.” Only by recognizing their blindness and letting go of the family butsudan will Adventists discover God’s calling for them.

The many who already have dared to let go of the Adventist butsudan, have found awesome rest in a new identity: the uniqueness of bearing only the Lord’s name rather than of carrying a denominational name or a church history. Letting go of the altar and embracing the gospel alone has brought these people spiritual joy, peace, and freedom from the confusion of trying to harmonize the opposing beliefs of the gospel and Adventist history.

Here in Japan, families who’ve thrown out the butsudan for Christ can tell you that it is difficult at first. But finding their identity in Christ alone has been worth it all. They learned the truth of His words: “Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 10:39). And what a life is waiting to be found in Him! †

Endnotes

- Kang Chol-Hwan and Pierre Rigoulot, The Aquariums of Pyongyang

- Ellen G. White, Early Writings, p. 139, 232-234; Spiritual Gifts, Vol. 1, p. 136, 140, 142. See also, Ratzlaff, The Cultic Doctrine of Seventh-day Adventists, “Right is Wrong, Wrong is Right”.

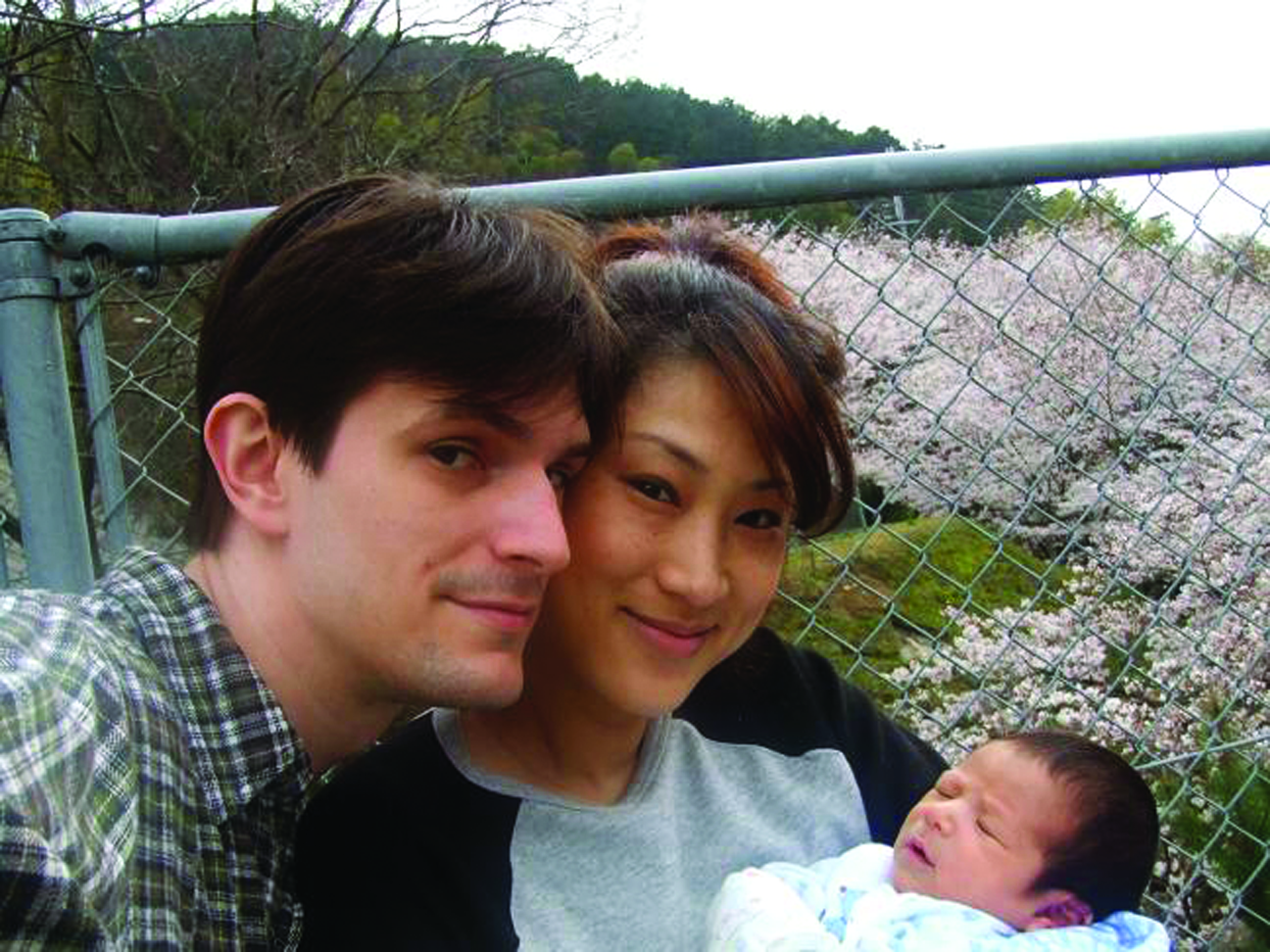

Ramone Romero was born a fourth-generation Adventist, grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, and served as a missionary for the Osaka Center Adventist Church. After being guided through the gospel of God’s grace and meeting the Holy Spirit, he found his rest in Jesus. Today he lives in Japan.

—Republished from Proclamation!, May/June, 2007.

- Who’s Teaching Another Gospel? - July 3, 2025

- Worship Jesus Because He Is - June 5, 2025

- Giving Up the Family Altar - May 29, 2025