[MARGIE LITTELL]

Hebrews is an interesting book written to the same people who cried for Jesus to be crucified, and it was written to them after Jesus returned to heaven.

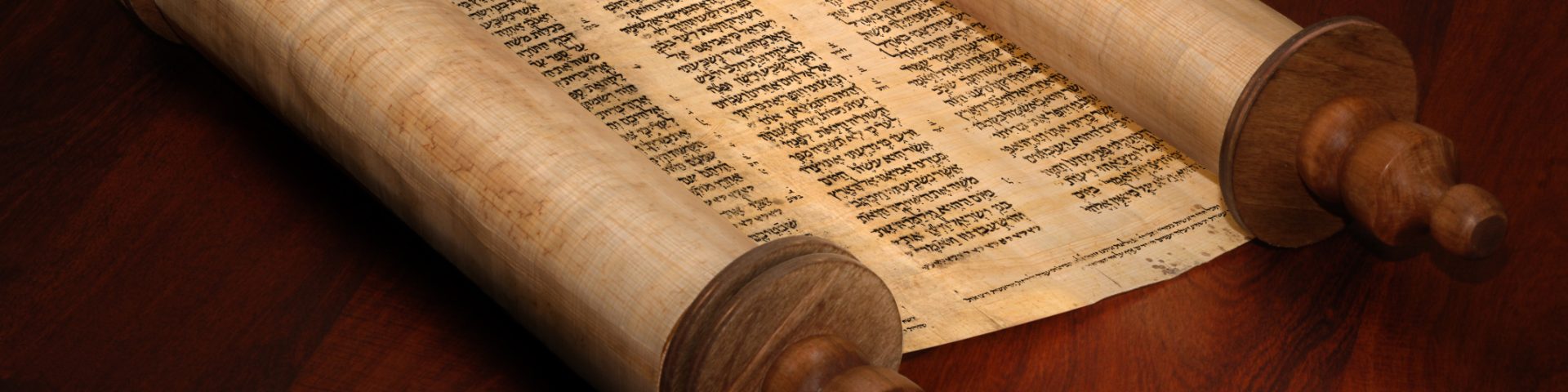

The message in this letter to the Hebrews is about the differences between their old and new covenants, and it explains how Jesus is greater than every part of the old covenant. Let’s start by reading God’s statement that the new covenant He promised would be different from the old:

It will not be like the covenant I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to lead them out of Egypt, because they broke my covenant, though I was a husband to them (Jeremiah 31:32).

The explanation of how this covenant is different is contained in the book of Hebrews, and this detailed explanation was written to the people who had been given the old covenant and its words. In chapters 7 through 10, the author explains clearly why the old covenant is now obsolete and why the new covenant is better and completely different.

Following is an outline of details you need to notice as you read this letter of Hebrews, but before you read it, we need to remember that the new covenant does not contain the Ten Commandments—and the Ten Commandments are the very words of the old covenant:

Moses was there with the Lord forty days and forty nights without eating bread or drinking water. And he wrote on the tablets the words of the covenant—the Ten Commandments (Exodus 34:28).

Why the Old Covenant Was Replaced

1. No one kept the old covenant:

For if there had been nothing wrong with that first covenant, no place would have been sought for another. But God found fault with the people and said: “The days are coming, declares the Lord, when I will make a New Covenant with the people of Israel and with the people of Judah” (Hebrews 8:7-8).

2. The old covenant is now obsolete:

By calling this covenant “new,” He has made the first one obsolete; and what is obsolete and outdated will soon disappear.

3. Changing the priests means changing the covenant’s law:

If perfection could have been attained through the Levitical priesthood—and indeed the law given to the people established that priesthood—why was there still need for another priest to come, one in the order of Melchizedek, not in the order of Aaron? For when the priesthood is changed, the law must be changed also (Hebrews 7:11-12).

4. Jesus, as our High Priest, became the Mediator of a superior covenant:

But in fact the ministry Jesus has received is as superior to theirs as the covenant of which He is mediator is superior to the old one, since the New Covenant is established on better promises. For this reason Christ is the mediator of a New Covenant, that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance—now that he has died as a ransom to set them free from the sins committed under the first covenant (Hebrews 9:15).

5. The new covenant is a promise made by God to Jesus:

And it was not without an oath! Others became priests without any oath, but He became a priest with an oath when God said to him:

“The Lord has sworn and will not change His mind: ‘You are a priest forever.’”

Because of this oath, Jesus has become the guarantor of a better covenant (Hebrews 7:20-22).

6. The new covenant’s salvation is complete, permanent, and forever:

Now there have been many of those priests, since death prevented them from continuing in office; but because Jesus lives forever, He has a permanent priesthood. Therefore, He is able to save completely those who come to God through Him, because He always lives to intercede for them (Hebrews 7:23-25).

7. Jesus’s sacrifice cleansed us once, not over and over as we continue to sin.

The law is only a shadow of the good things that are coming—not the realities themselves. For this reason it can never, by the same sacrifices repeated endlessly year after year, make perfect those who draw near to worship.Otherwise, would they not have stopped being offered? For the worshipers would have been cleansed once for all, and would no longer have felt guilty for their sins. But those sacrifices are an annual reminder of sins (Hebrews 10:1-3).

Peter repeats this certainty:

For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, to bring you to God. He was put to death in the body but made alive in the Spirit (1 Peter 3:18).

8. Jesus Christ’s sacrifice was sufficient to take away all our sins once and for all:

Otherwise, Christ would have had to suffer many times since the creation of the world. But He has appeared once for all at the culmination of the ages to do away with sin by the sacrifice of Himself. Just as people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment, so Christ was sacrificed once to take away the sins of many; and He will appear a second time, not to bear sin, but to bring salvation to those who are waiting for Him (Hebrews 9: 26-28).

John confirms this fact in several places including John 1:29 where John the Baptist declares, “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” Jesus’ completed atonement is further emphasized in John 17 and in 1 John 2:1-2.

9. Jesus’s one and only death on the cross gives us access to God and full assurance:

Therefore, brothers, since we have confidence to enter the holy places by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain, that is, through his flesh, and since we have a great priest over the house of God, let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, with our hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water (Hebrews 10:19–22).

In conclusion, Adventism is not “spiritual Israel” entrusted with the law to prove it can be kept and thus vindicate God. Rather, the law has become obsolete by the life, death, burial, resurrection, and ascension of the Lord Jesus. He is greater than every shadow of the law, and His blood is the guarantee of God’s new covenant.

When we gentiles trust Jesus’s finished work, we also are grafted into the new covenant—but being partakers of the new covenant does not make us “Israel”. Instead, the Lord Jesus has created something completely new, one new man in Himself—and He is the One we worship and obey.

Jesus, not the law, is our object of worship and obedience, and we rejoice in the new covenant in His blood. †

- Jesus Broke the Sabbath and Declared Himself God - February 22, 2024

- God Told Daniel the Future - January 18, 2024

- A New Covenant Needs New Words - November 23, 2023

Your article correctly points out the differences between the old and new covenants, but it does not at all address whether or not the New Testament church (or SDA church for that matter) is the continuation/fruition of Israel.

Christians individually considered and the Church as a collective body are called by distinctively Jewish names: “For he is not a Jew, which is one outwardly; neither is that circumcision, which is outward in the flesh: But he is a Jew, which is one inwardly; and circumcision is that of the heart, in the spirit, and not in the letter; whose praise (Judah) is not of men, but of God” (Rom. 2:28-29).

Christians are called “the circumcision”: “For we are the circumcision, which worship God in the spirit, and rejoice in Christ Jesus, and have no confidence in the flesh” (Phil. 3:3).

We are called “the children” and “the seed of Abraham”: “Know ye therefore that they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham…. And if ye be Christ’s, then are ye Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise” (Gal. 3:7, 29).

We are of the “Jerusalem which is above” and are called the “children of the promise” (Gal. 4:24-29). In fact, Christians compose “the Israel of God” for we are a “new creature” regarding which “circumcision availeth nothing” (Gal. 6:16).

James designates Christians as “the twelve tribes which are scattered abroad” (Jms. 1:1). Peter calls the Christians to whom he writes, the “diaspora” (Gk., 1 Pet. 1:1). Paul constantly calls the Church the “Temple of God” which is being built in history as men are converted (1 Cor. 3:16-17; 1 Cor. 6:19; 2 Cor. 6:16; Eph. 2:21).

Peter follows after Paul’s thinking, when he designates Christians you as “stones” being built into a “spiritual house” (1 Pet. 2:5-9). He also draws upon several Old Testament designations of Israel and applies them to the Church: “a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation.” (1 Pet. 2:9-10; Exo. 19:5-6; Deut. 7:6). He, with Paul, also calls Christians “a peculiar people” (1 Pet. 2:10; Tit. 2:14), which is a common Old Testament designation for Israel (Deut. 14:2; 26:18; Psa. 135:4).

God has always had only one covenant people, and it was a mixed multitude from its beginning. The remnant of Israel accepted Christ, the rest were broken off because of their unbelief, and the Gentiles were grafted in, and IN THIS WAY (with the inclusion of the Gentiles) ALL Israel will be saved. The terms of being in Israel changed, but God does not have two brides.

Jsaras, your comments above reveal the divide between viewing the church through the framework of “covenant theology” vs. non-covenant theology. Even the newer “system” of theology called “new covenant theology” bases its view on the covenant theology framework.

In a nutshell (and I admit there may be many details involved in explaining the differences that I will not be able to address), covenant theology is the framework handed down to us by many of the reformers. Interestingly, perhaps the foundational difference between covenant theology’s understanding of history and prophecy and the non-covenant theology understanding is that, while both views regard a literal reading of Scripture to be the proper hermetic for understanding God’s word, the covenant theology framework tends to approach prophecy with a more symbolic or allegorical reading. In other words, covenant theology reads Scripture literally until it gets to prophecy, either OT or NT, and there it resorts to a symbolic reading. A non-covenant theology view persists in using a historical-grammatical literal reading.

Another difference is that the covenant theology framework establishes an understanding of “covenant” that is not described in Scripture. For example, it uses a grid of something called a “covenant of grace” and some even say there was a “covenant of works” before the fall. And so on. This assumption that all of God’s work throughout history can be evaluated through the grids of covenants that are never actually described in Scripture leads ultimately to a different understanding of how God’s people and God’s work in the world should be understood. This underlying “covenant theology” leads also to a less literal understanding of the Mosaic covenant and ends up retaining the Law (Decalogue) as a rule of faith and practice for the church.

And so on.

Now, I have oversimplified this explanation, and clearly there are differences among those who believe in a covenant theology framework. Yet all to say, I understand what you are saying above, but I do not see Scripture as being defined and organized by “covenant theology”. I believe that when God says He made covenants, those are the covenants we must consider to be “real”. I do not believe we can “create” covenants where God doesn’t say He made one (such as a “covenant of works” or a “covenant of grace”). Therefore, when the Bible uses words, we need to read them using normal rules of grammar and vocabulary, and we read them in the normal way. Otherwise we impose meanings on them that the first audience would never have understood and which are not implicit in the text.

I just want to mention a few points in your post above. First, when James addresses his epistle to “the twelve tribes which are scattered abroad”, we have no reason to say this phrase applies to the the church at large. James , the head of the fledgling church in Jerusalem, was writing to believers, but we can tell from the Jewish nature of his letter that he was writing to Jewish believers. (Many believe this letter was written before AD 50, and James was writing during the very early years when the church was still mostly Jewish.) When he refers to the “twelve tribes”, he is referring to Jews. The church is never referred to as the twelve tribes. In other words, James is writing to the exiled Jewish believers who, along with the still-orthodox Jews, were being exiled from Jerusalem throughout the Roman empire because of persecution. The believers among the exiles were displaced—both geographically and spiritually—as they found themselves among their Jewish kinsmen but no longer Old Testament Jews. They were born again and filled with the Spirit, but they were living among Jews who were still married to the law.

This is perhaps the first NT letter written—possibly with the exception of Galatians—and James is writing to encourage those Jewish believers and to remind them that they now live under the “royal law”, the “law of liberty” instead of the law that sentenced them to death (James 2:1–13). He was encouraging them to live according to the wisdom from God and not to become caught up in the social and legals disputes common in Jewish communities.

James is clearly writing to JEWS—believing Jews—while the church is still primarily Jewish. He is not addressing gentiles specifically. The first audience is crucial in our understanding of what an author was actually saying. It is clear, when we read his words literally, using normal rules of grammar and vocabulary, that he is addressing Jews—specifically Jews who are new believers but are still caught in Jewish communities but who are exiled away from their familiar Judah and are now living in hostile Roman territories.

If, however, we decide to spiritualize the words “the twelve tribes” and apply that to the whole gentile and Jewish church, we literally change the meaning of James’s audience and message. Of course we can make application to us as gentile believers, but he is writing to Jewish believers. We need to believe his actual words to mean what he actually says. The first audience is critical to our understanding of an author’s intent.

Further, the fact that Peter designates Christians as “stones” being built into a “spiritual house” does not mean that Peter is now saying Christians can be considered spiritual Israel because of the phrases like “royal priesthood” and “holy nation”. The fact that Israel was a holy nation and a peculiar people does not mean that the church must now be considered “spiritual Israel” because Peter uses those phrases of the church. In fact, Paul, in Ephesians 2:19–22 uses the building metaphor of the church. He calls the church “one NEW man” in verse 15 (note he calls the church completely, utterly NEW–not a continuation or extension of Israel but one NEW man in Jesus), and then he says God is building the church into “a holy temple in the Lord, in whom you also are being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit” (v. 21, 22).

Paul is not describing “spiritual Israel” by using the temple metaphor. He is describing a completely NEW creation (see also 2 Cor. 5:17—the old things are passed away, the new things have come). God’s words and shadows for Israel defined them apart from the surrounding nations, and God uses many of those same words to explain the new role of the church—but those words and concepts have new life now because Jesus fulfilled the shadows of those concepts of temple, priest, sacrifice, etc, and the new creation who is alive in Christ is a different kind of “holy nation” and “royal priesthood”. The church is alive in Christ with the permanently indwelling Holy Spirit. Our identity is different from Israel—although both they and we are God’s people. Both have specific identities and jobs and roles in God’s eternal story, and God loves them all. But we can’t blur their identities and make them essentially the “same thing”.

As for God having only one “covenant people”—that is not the way Scripture describes God’s people. Israel was God’s chosen nation because God chose them, and He made his Mosaic covenant with them. When Jesus came and inaugurated the new covenant in His blood, He fulfilled that old covenant and created a whole new creation in Himself of believing Jews and gentiles. To be sure, all who believe are the seed of Abraham—Romans explains this fact in detail, and Romans 4 is explicit that the faith of Abraham preceded his circumcision, making him the “father of faith” of ALL who believe. Yet Paul goes on in Romans to say that a temporary partial hardening has hardened Israel until the full number of gentiles comes in. (And just BTW, God had believing people BEFORE Abraham as well: Abel, Enoch, Noah—we can’t say God’s people have always been a “mixed multitude”. Even though a mixed multitude left Egypt, when the law was given, non-Jews who wanted to worship Israel’s God had to become Jews. They had to be circumcised and submit to the law. God’s people have always been those who submitted to whatever His revelation of Himself was at any given time.)

He also says (Romans 11) that God’s calling and His promises are irrevocable. God will still keep His promises to Israel—not on the basis of the Mosaic covenant, but on the basis of His promises to Abraham/the patriarchs.

All to say, covenant theology requires a more allegorical method of reading prophecy, but I believe that the more literal our hermeneutic, the more literal we are in understanding what the author said and what the first audience would have understood—those things must inform us. We can’t change the meanings of the words to fit our perception at this point in history. I have to believe that God means what He says and says what He means. Even if I don’t understand all the details, I have to know that when the Bible tells me the church is something completely NEW, CREATED using the words of Genesis) in Christ, God means exactly that. The church is NEW. It is composed of Jews and gentiles, and it is not an extension of Israel. Furthermore, when God makes promises to Israel that have not yet been fulfilled, then according to Paul himself, those promises are irrevocable. I may not see how or when they will come to pass, but God cannot lie. He doesn’t morph His promises and change the recipients.

He grafts us into the new covenant, and He is faithful to His own word.

No, Jesus does NOT have two brides. Yet He does have different peoples at different times, and interestingly, in Revelation 21:12–14, when John see the Holy City descending from heaven in the eternal state, the gates have the names of the twelve tribes of Israel, and the foundation stones contain the names of the twelve apostles. Ultimately all of God’s people will be together in that city (and interestingly, the city is adorned as a bride—yet we KNOW that Jesus is not married to buildings but rather to PEOPLE!), but for all eternity there will be the reminder of the two people: God’s pre-cross nation of Israel, and His church founded by the apostles. He doesn’t blur us all together.

I can’t explain it fully, but when I see the NT making distinctions between Israel and the church, I have to believe those mean something. God has different assignments and time-lines for each, and He is faithful to His own promises. Israel isn’t now “null and void”; they are partially hardened for a time (Romans 11 again). What unites us all is belief in God and His word. Abraham is the prototype of all who are saved: their belief is credited as righteousness. What Abraham and David and the heroes of faith in Hebrews 11 believed was God Himself. They acted on what He said because they believed Him. What we believe on this side of the cross is still God Himself—but now He asks to specifically to believe in HIS SON—God Himself—who propitiated for our sin.

At the bottom line, I believe hermeneutics is the issue that defines and clarifies our points of view. I personally find it easiest to study and understand Scripture using a consistent hermetic of believing the words matter and context is everything. I can’t go back and forth between literal and figurative depending on the genre of the book or on the questions that I have. But I do trust God to be consistent and faithful. Even what I don’t understand will become clear in His time. I know He will straighten out my misunderstandings in His time and way!

The “consistent hermeneutic” argument is a red herring. . For example, all dispensationalists find a gap of thousands of years between Daniel’s sixty-ninth and seventieth “weeks,” though there is certainly nothing in Daniel 9 which, taken literally, would require or justify this. Dispensationalists also insert a gap of two thousand years at a comma between two clauses in Isaiah 61:2. This gap is not suggested by any literal reading of the text. Like everybody else, dispensationalists do not believe that Jesus is a literal “Lamb…having seven horns and seven eyes” (Rev. 5:612), nor that the Devil is literally a seven-headed reptile (Rev. 12:9), nor that the world will worship a ten-horned wild animal (Rev. 13:1–4). A strictly “literal” approach to Revelation would require such a reading, but no one is so foolish as to insist on such “consistency.”

The most accurate way to state the case is that all biblical interpreters interpret some things literally, and some figuratively. The dispensationalists are not more consistent than are the non-dispensationalists in the application of a literal hermeneutic—nor is that necessarily a criticism. The incongruity would seem to be in the dispensationalist’s claim to differ from others in this respect.

I take the Apostles interpretations of OT prophecy fulfillment as definitive. Often times, when one reads the original OT prophecy and compare it to its fulfillment, it doesn’t seem to align with my logic, but I defer to them.

In Romans 9:6 Paul says that “not all who are of Israel are Israel.” This indicates the existence of two “Israels”. One—”all who are of Israel”—indicates the ethnic people, not all of whom believe in Jesus. The other Israel, the context reveals, does not include those who have rejected the Messiah. This new Israel, founded by Messiah, exists in spiritual continuity with the Old Testament saints and so counts as a “spiritual Israel.” It includes Gentiles who believe in the Messiah and so through baptism are spiritually circumcised (Col. 2:11–12) and are reckoned as spiritual Jews (Rom. 2:26–29).

In his letter to the Ephesians Paul is even more explicit about the Gentiles’ spiritual inclusion when he states that “you Gentiles in the flesh . . . were [once] separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel . . . But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near . . . So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the saints” (2:11–13, 19. It cannot possibly be clearer than that. Why do you not take THAT literally. It’s likely because of a prior commitment to making everything fit into a preconceived theological system.

Some of the other arguments you made do not negate my position at all, which may indicate agreement. These types of exchanges are difficult in this format.

Thank you for the clear, concise explanation!

“Now to Abraham and his Seed were the promises made. He does not say, ‘And to seeds,’ as of many, but as of one, ’And to your Seed,’ who is Christ” (v. 16). Also: “What purpose then does the law serve? It was added because of transgressions, till the Seed should come to whom the promise was made” (v. 19).

These verses nullify the claim of any race to being “the seed” . Paul is emphatic that there are not multiple seeds, and that no race or family (e.g., ethnic Israel) need apply. There is one Seed, whom Paul identifies as Christ . Christ is the promised Seed. The promises are His alone.

Then Paul says “And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise” (v. 29). Christ is the one Seed of Abraham who is the heir of the promises—and so are we, if we are in Him. We are all one (the one “Seed”) in Christ.

Christ and the church are one organism. Christ is the Head, Christians are the body, and together we form “one new man” (Eph. 2:15), which is “Christ” (1 Cor. 12:12), and is itself the one Seed that can lay claim to the Abrahamic blessing. We are the “heirs according to the promise” given to Abraham and his Seed.

To be a child of Abraham is not a matter of genetics (Rom. 2:28–29; 9:8; cf. Matt. 3:9), but rather of having the faith that Abraham had (John 8:39, 56). “Just as Abraham believed God…know that [only] those who are of faith are sons of Abraham” (Gal. 3:6).

In the same chapter Paul also clarifies the “blessing” that is so prominent in Genesis 12:1–3. This he identifies with the blessing of receiving, by faith, justification and the gift of the Holy Spirit. The blessing is salvation through Christ. “God would justify the Gentiles by faith…So then those who are of faith are blessed with believing Abraham…that the blessing of Abraham [justification] might come upon the Gentiles in Christ Jesus, that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith” (vv. 8–9, 14).

The Abrahamic Covenant is the Gospel of salvation through Jesus Christ. “Foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, [the Scriptures] preached the gospel to Abraham” (Gal. 3:8).

Jsaras, I am not trying to defend Dispensationalism. I frankly have not studied Dispensationalism and cannot defend it nor explain it. I just know that when I read Scripture using the normal rules of grammar and vocabulary and context, “things” hang together better than using other methods.

For example, when I say I use a “literal” or “normal” consistent hermeneutic, I do not mean that I don’t recognize when the text is using figurative language. Of course normal writing includes similes, metaphors, allegories, and so forth as a normal feature of language. A literal reading does not mean interpreting these figures of speech into literal applications any more than a literal reading of Shakespeare would require my reading his extensive metaphors as literal applications. (Lady MacBeth certainly was not literally attempting to remove blood from her hands as she cried, “Out, out, damned spot!”) Neither does a literal reading mean that the beasts of Daniel and Revelation are literal animals. What a literal reading does mean, though, is that I have to read these figures of speech and, using the contextual explanations, understand that they represent qualities and ideas that describe human and/or spiritual powers.

However, a consistent hermeneutic would also mean that I couldn’t designate clear promises of God, especially in the OT prophets, for example, and say that, because there has been no actual physical fulfillment of those promises yet, that they are figurative and have spiritualized applications. That application changes the meanings of the words and of the promises of God. I can’t explain all of the prophecies clearly, and I am not attempting to insert time periods between commas or timelines. I don’t actually know those particular traditions.

I agree with you that Christ and the church are one organism. Paul is very clear, with his metaphor of Christ being the head and of the church being the body, that this idea is the case. I agree that being heirs of Abraham has nothing to do with genetics but has everything to do with BELIEVING as Abraham did—and on this side of the cross, that belief means believing in Jesus. The Abrahamic covenant is truly eternal and unconditional—and the new covenant explains the details of the Abrahamic promises more fully. Yet the promises God made to Abraham were not only spiritual. There were physical promises that were made, and they have not all been fulfilled. God has worked with humanity over the millennia in different ways at different times, and I believe that He is not yet done doing so.

In spite of His different methods and times, though, the way He saves has always been the same: those who believe are counted righteous—and that promise and that accrediting are not dependent upon our gene pools. They are entirely the result of responding to our Sovereign God when He gives us faith to believe and asks us to believe!