RICHARD TINKER | COLLEEN TINKER | STEVE PITCHER

About five years ago Richard and I sat with our older son Roy in a Bible class on the campus of Biola University in La Mirada, California. Roy was considering attending Biola, and we were experiencing college day with him. We had officially left the Adventist church only two years before, and this was our first experience on an evangelical Christian college campus.

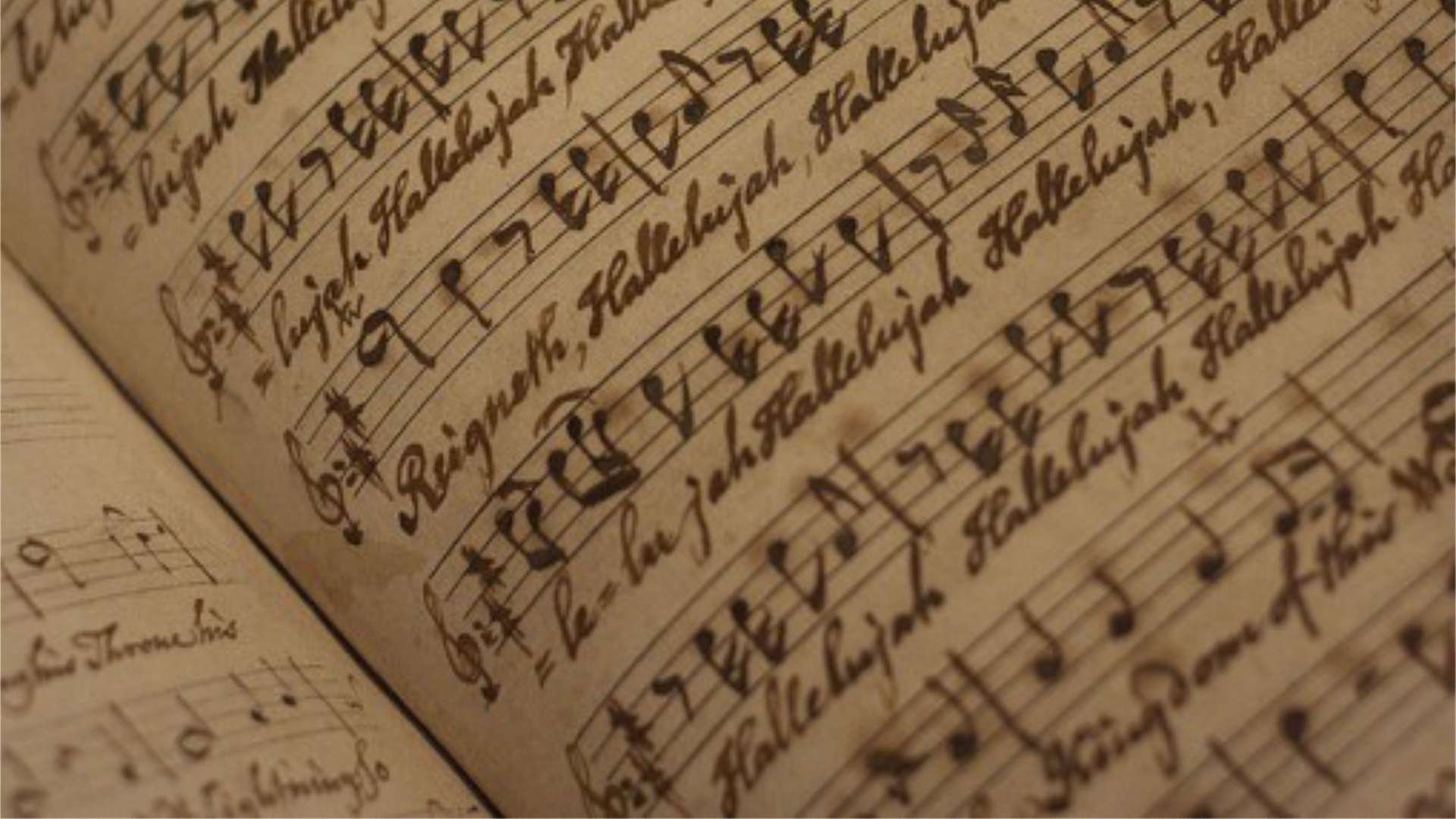

The teacher called the class to order and said, “Please reflect on the hymn you see on the screen. We’ll discuss it after you’ve had a few minutes to think about it.”

We looked up, and projected in front of the class were these words:

Come, Thou Almighty King

Come, Thou almighty King,

Help us Thy Name to sing Help us to praise!

Father all glorious, over all victorious,

Come and reign over us, Ancient of Days!

Come, Thou incarnate Word,

Gird on Thy mighty sword, our prayer attend!

Come, and Thy people bless, and give Thy Word success,

Spirit of holiness, on us descend!

Come, holy Comforter,

Thy sacred witness bear in this glad hour.

Thou Who almighty art, now rule in every heart,

And ne’er from us depart, Spirit of power!

To Thee, great One in Three,

Eternal praises be, hence, evermore.

Thy sovereign majesty may we in glory see,

And to eternity love and adore!

The words were familiar—and somehow unfamiliar. As I read the stanzas, I realized for the first time that this hymn is an invocation to the Trinity. I felt like crying as I realized the powerful declaration of both God’s transcendence and immanence this hymn contained. Why had I never noticed the reverent worship offered to the Trinity in this song?

Changed Words

“Come, Thou Almighty King” was the second hymn I had sensed was different from the way I originally learned it. The first was “Holy, Holy, Holy.” Here are the words:

Holy, holy, holy! Lord God Almighty!

Early in the morning our song shall rise to Thee;

Holy, holy, holy, merciful and mighty!

God in three Persons, blessed Trinity!

Holy, holy, holy! All the saints adore Thee,

Casting down their golden crowns around the glassy sea;

Cherubim and seraphim falling down before Thee,

Who was, and is, and evermore shall be.

Holy, holy, holy! Though the darkness hide Thee,

Though the eye of sinful man Thy glory may not see;

Only Thou art holy; there is none beside Thee,

Perfect in power, in love, and purity.

Holy, holy, holy! Lord God Almighty!

All thy works shall praise Thy Name,

In earth and sky and sea;

Holy, holy, holy; merciful and mighty!

God in three Persons, blessed Trinity!

Puzzled by the fact that these words seemed both familiar yet strange at the same time, I finally looked up the song in the current edition of the Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal published in 1985. The song appeared almost as it appears above. Verse two, however, had been altered to read “Angels adore Thee” instead of “All the saints adore Thee,” and the third line of the same verse had been changed to “Thousands and ten thousands worship low before Thee.” Similarly, the second line of the third stanza had been altered to read: “Though the eye of man Thy great glory may not see.”

Then, on a hunch, I looked up the hymn in the preceding edition of the Adventist hymnal—the one published in 1941 and used until the 1985 version was released. This older version was the one I had sung from during my years growing up in the church.

Sure enough—I found even more radical changes. The first verse was the same as it appeared in the new edition with this exception: instead of the fourth line—“God in three Persons, blessed Trinity!”—the old edition had these words: “God over all who rules eternity!” The fourth stanza was missing entirely.

I realized with sudden clarity that until 1985, the Adventist church had been singing this well-known hymn of the faith with references to the Trinity completely obliterated from it. Not only that, the hint that God’s people who have died might be praising Him even now had been eliminated (verse 2), and this elimination persisted to the present time. (This idea had to be eliminated in order to preserve the doctrine of soul sleep for Adventist worshipers.)

Antitrinitarian Roots are Showing

It is a fact the church admits (but does not often publicly discuss) that the founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, including James White (Ellen’s husband), were staunch anti-Trinitarians. Ellen White never really clarified whether or not Jesus was eternally divine. She did write several statements about Jesus originally being an angel and God elevating Him to a position of authority and sonship. Sometimes her statements revealed confusion about Christ’s identity.

“The man Christ Jesus was not the Lord God Almighty, yet Christ and the Father are one. The Deity did not sink under the agonizing torture of Calvary, yet it is nonetheless true that ‘God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.’” (Lift Him Up, page 235, paragraph 3, copyright1903).

“The highest of all angels, He girded Himself with a towel, and washed the feet of His disciples” (Manuscript Releases, Volume Twelve, page 400, par. 1).

“Before his fall, Satan was, next to Christ, the highest angel in heaven” (Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, 01-14-1909, Paragraph 4).

“God is the Father of Christ; Christ is the Son of God. To Christ has been given an exalted position. All the counsels of God are opened to His Son” (Testimonies for the Church, Volume 8, page 268, par. 3).

Her book Desire of Ages (published in 1898 and more recently proven to contain large percentages of plagiarized material; see “Recant, No! I Stand Firm” by Walter Rea, Proclamation!, November December, 2004) became the turning point in the Adventist understanding of the Trinity. Although many statements in Desire of Ages were clearly trinitarian, Ellen White continued to publish non-trinitarian statements in succeeding years as noted above. The church’s first administrative affirmation of the Trinity did not occur until 1931, and that statement was not accepted as an official Adventist doctrine until the General Conference session in 1946. In 1980 a more comprehensive, classical Trinitarian statement was adopted at the General Conference session in Dallas. Interestingly, however, the 1980 statement triggered “renewed debate along a spectrum of ideas from the reactionary to the contemporary.”(“The Adventist Trinity Debate,” Jerry A. Moon, Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol 41, No. 1, p. 9, copyright 2003)

While Adventism today claims to hold a belief in the Trinity and includes it in the 27 Fundamental Beliefs, still the way Adventists understand the Trinity is murky. Among contemporary Adventist theologians, authors including Raoul Dederen, Fernando Canale, Richard Rice, and Fritz Guy have published statements questioning classical Trinitarian theology. (ibid., p. 9-10) Their observations reveal that there is no consensus among Adventist intellectuals and theologians regarding the Trinity.

One current view suggesting a tritheistic understanding appeared in the October 31, 1996 issue of the Adventist Review, the “flagship journal” of the church. Written by Gordon Jenson, it appeared on page 12: “A plan of salvation was encompassed in the covenant made by the Three Persons of the Godhead, who possessed the attributes of Deity equally. In order to eradicate sin and rebellion from the universe and to restore harmony and peace, one of the divine Beings accepted, and entered into the role of the Father, another the role of the Son. The remaining divine Being, the Holy Spirit, was also to participate in effecting the plan of salvation.”

The antitrinitarian roots of Adventism still color the church’s doctrines today. Perhaps because the original Adventist view of Jesus described Him as inherently lower than God, Adventists still have trouble exalting him to an all-powerful, sovereign position. Similarly, Adventists also have trouble embracing the terrible reality of Jesus’ shed blood and our total dependence upon Him.

Realizing that the Adventist version of the hymn “Holy, Holy, Holy” betrayed the foundational anti-Trinitarian belief of Adventism (as well as, I discovered, the current questioning of the doctrine), I became curious about other hymns as well.

Sunday Discovery

One Sunday afternoon last summer, Richard and I sat at our kitchen table with our friend Steve Pitcher and began our pursuit of the truth about Adventist hymnology. Armed with the current 1985 edition of the Adventist hymnal, the previous 1941 edition, and a non-Adventist Christian hymnal, we began comparing the words of hymns. Thinking we would find that the heresies written into some of the hymns of the 1941 edition would be corrected in the 1985 edition, we were not prepared for what we found. While some of the more blatant eradications of the Trinity were corrected in the 1985 edition, others were not. Still more astonishing, the newer edition contained editorial changes which downplayed the atonement and the blood of Jesus even more than the earlier edition had done.

Finally, after we three spent several hours on two separate Sundays comparing hymns and making notes, I went to the internet* and found the original poems for all the hymns in question just to make sure that the non-Adventist hymnal we used hadn’t been edited in some way.

The first hymn we compared was the one that had moved me so deeply that morning at Biola: “Come, Thou Almighty King”(words often attributed to Charles Wesley). At last I knew why it had so amazed me. The 1985 edition of the hymnbook contained the standard words, but the 1941 edition completely eliminated the second stanza about the Incarnate Word, and a substitute verse replaced the last stanza honoring the “great One in Three”:

Thou are the Mighty One,

On earth Thy will be done; from shore to shore,

Thy sovereign majesty, may we in glory see

And to eternity love and adore.

Again, until 1985, the Trinity had been completely missing from this song. Not only the Trinity, but the stanza about Jesus being the incarnate Word had likewise been omitted.

Amazed, we continued our search. We discovered that the hymn “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross”(words by Isaac Watts) had likewise been updated in the 1985 edition. In the 1941 edition, this stanza with its direct reference to the divinity of Jesus had been left out:

Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast,

Save in the death of Christ my God!

All the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them to His blood.

While the stanza was replaced in the 1985 edition, both books eliminated the following verse which underscores Jesus’ suffering and shed blood:

His dying crimson, like a robe,

Spreads o’er His body on the tree;

Then I am dead to all the globe,

And all the globe is dead to me.

The hymn known to Adventists as “Praise Ye the Father”(words by Elizabeth Charles), we discovered, is a paean to the Trinity and is actually entitled “Praise Ye the Triune God”. Both editions of the Adventist hymnal contained all the original verses with one alteration. In both, the last line of the third stanza, “Praise ye the Triune God”, was changed to “Praise the Eternal Three”. It seems a nearly insignificant change, but it promotes a more tritheistic view than a trinitarian view. Further, the phrase “Triune God” has been eliminated from the title as well.

We also found less obvious but no less significant alterations downgrading the supremacy of Jesus in other hymns as well. We discovered that the hymn “I Need Thee Every Hour”(words by Annie S. Hawks) had been faithfully printed in the 1941 edition of the Adventist hymnal. In the updated 1985 edition, however, the last stanza, which stresses the divinity of Jesus and our absolute dependence upon Him, is eliminated:

“I need Thee every hour, most Holy One;

O make me Thine indeed, Thou blessed Son.”

More Changes

“Now the Day Is Over” is a poem written by Sabine Baring-Gould set to a tune by Joseph Barnby. It contains six short stanzas. In both editions of the Adventist hymnal, stanzas three, five, and six are missing. Stanza five expresses the confidence we have that as believers we stand sinless in the eyes of God:

When the morning wakens,

Then may I arise

Pure and fresh and sinless

In your holy eyes.

Leaving out stanza five accommodates two Adventist beliefs stressed by Ellen White. The first is that the atonement is not yet complete because Jesus is still applying His blood in the heavenly sanctuary. The second is that it is presumption to say we are saved. We cannot be certain of our salvation until Jesus comes again.

Stanza six is a doxology praising the Trinity. Significantly, it, too, is missing:

Glory to the Father,

Glory to the Son,

And to you, blest Spirit,

While the ages run.

One other significant change in both editions of the Adventist hymnal occurs in verse two. The original poem reads, “Jesus, give the weary/Calm and sweet repose…”The Adventist version changes “Jesus” to “Father”, thus subliminally reinforcing the belief that the Father, not Jesus, is truly our God.

With two similar editorial changes, the hymn “Standing on the Promises” (text and tune by R. Kelso Carter) diminishes the supremacy and all-sufficiency of Jesus. The song is completely missing from the earlier edition of the Adventist hymnal. The 1985 edition, however, contains the following alterations.

In the original chorus, the text reads: “Standing, standing, standing on the promises of Christ my Savior/standing, standing, I’m standing on the promises of God.”

The Adventist version, however, changes the beginning of the chorus to read thus: “Standing, standing, standing on the promises of God [as opposed to Christ] my Savior.” Further, the last of the songs’ four stanzas is missing in the Adventist hymnal. It reads:

“Standing on the promises I cannot fall,

listening every moment to the Spirit’s call,

’resting in my Savior as my all in all,

standing on the promises of God.”

A final example of the Adventist hymnal’s tampering with the orthodox Christian belief about the nature and identity of Jesus occurs in the hymn “On Jordan’s Stormy Banks I Stand.” Written by Samuel Stennett, the text contains seven stanzas. In both editions of the Adventist hymnal, four of the seven are omitted albeit without significant theological consequences. The real problem, however, is in stanza four (stanza two in the Adventist books). Lines three and four of the original read, “There God the Son forever reigns,/And scatters night away.”

In the Adventist books, however, “God the Son” is changed to “Christ the Sun”. Because of the homonym Son/Sun, the change would be nearly undetectable if one only heard the words. In reality, however, the Adventist text deliberately refuses to equate “God” with “Son”—not merely in the older edition of the hymnal, but in the currently used book. An antitrinitarian bias is still at work in Adventist doctrines.

Hymns Reflect Doctrines

It remains for future articles to examine other hymns which Adventists have edited. Some modify or downplay Christ’s suffering and His complete atonement for our sins. Others perpetuate the doctrine of soul sleep by eliminating or changing references to meeting God when we die or to saints being present with Him now. Still others remove references to being part of the historic church in order to maintain the illusion that Adventists are the remnant people of God who are called out of the Babylon of apostolic tradition and “apostate Protestantism”.

In a time when Adventists are actively promoting themselves as a mainstream evangelical church (without actually adopting evangelical doctrines), their hymnal continues to reveal the truth about the church’s beliefs. People remember the words of songs long after they have forgotten the words of specific sermons or doctrinal classes because lyrics are attached to tunes. Because Adventist churches all use the same official hymnal (when they’re not branching into praise music), every Adventist is being subliminally taught and reinforced in the truly Adventist beliefs of a modified Jesus, a sanitized atonement, a God who “would never” express wrath, soul sleep, and their own status as God’s chosen remnant. Since most Adventists would not be likely to sing the hymns of the faith from any hymnal but their own, they would be unlikely to realize that many of the words they sing every Sabbath are not the words of Christendom in general.

A religion’s hymns reflect that religion’s distinctive beliefs. Doctrines that might be veiled in a church’s public statements and printed material will emerge in its hymnbook. Consequently, it is no mistake that the Adventist church has its own hymnal. If it used a generally available Christian hymnbook, it would be exposing its members to true Biblical Christianity that would conflict with what the church teaches.

Looking back on the songs of our youth, we can say with the psalmist,

“Sing to the Lord a new song; sing to the Lord, all the earth.

Sing to the Lord, praise his name; proclaim his salvation day after day.”

—Psalm 96:1-2, NIV

Richard and Colleen Tinker attend Trinity Evangelical Free Church in Redlands, California, where they also lead a Friday night Former Adventist Fellowship (FAF) Bible study. Their studies, as well as a collection of stories by former Adventists and a live discussion forum are online at: www.formeradventist.com.

Steve Pitcher, who became a Christ-follower and was baptized in a Baptist church at the age of seventeen, subsequently spent 15 years as a Seventh-day Adventist. He left Adventism in 2000 and currently attends Pathway Christian Church in Riverside, California. He also attends the weekly FAF Bible study in Redlands.

*www.cyberhymnal.org, www.hymnsite.com, www.oremus.org,

www.digitalhymnal.org, www.cgmusic.com, http://ingeb.org

- The Problem With Pride - February 8, 2024

- Now Is the Right Time to Claim Salvation - February 8, 2024

- Unmasking the Cultic Spirit - December 26, 2023

Colleen,

Thanks for this article. It is truly illuminating and disturbing at the same time.

For the information of your readers, here is an extract from the Liturgy of St James:

In the “Prayer of the (Celebrant) standing before the altar” (less than two minutes into the Liturgy) and the second substantive prayer of the Liturgy, we find this prayer:

“Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, the triune light of the Godhead, which is unity subsisting in trinity, divided, yet indivisible: for the Trinity is the one God Almighty, whose glory the heavens declare, and the earth His dominion, and the sea His might, and every sentient and intellectual creature at all times proclaims His majesty: for all glory becomes him, and honor and might, greatness and magnificence, now and ever, and to all eternity. Amen” (7ANF 537)

Notes:

1. The word (Celebrant) is not in the ANF publication, but is implied, and is designed to work within Paul’s framework of “presbyter” (priest) – see later headings in the ANF text.

2. At the outset, all the prayer except the “Amen” at the end was said by the Celebrant.

3. Likewise, the “Amen” at the end was initially said by all the gathered faithful, including the Celebrant.

Note on the Liturgy of St James:

Despite what some protestant scholars may say, this Liturgy is of Apostolic origin. Its basic structure and content was composed by St James the Just (Ya’akov ha Tzaddik) in or around the year 58CE in Jerusalem to address the worship-problems in the Corinthian congregation (1Cor 1:11, 11:17-22) and to give them a model of a full worship-exercise which transcended the barebones basics of 1Cor 11:23-34.

[1 Corinthians was written 54CE]

While the ANF text (pp 537-550) has minor later interpolations, this prayer is original to St James and reflects the belief of the remaining 11 Apostles.

This liturgy was for Gentile use in the central and eastern Mediterranean for those congregations evangelized by Paul, and was more or less the basis for the Liturgy of St Mark (of Alexandria) and Gospel Writer, written a year or two later, it was most definitely the origin of “the forty Syro-Jacobite offices: on the other, the Caesarean office, or Liturgy of St Basil, with its offshoots; that of St Chrysostom, and the Armeno-Gregorian” (7ANF 534).

“The offshoots from St Mark’s Liturgy are St Basil, St Cyril, and St Gregory* and the Ethiopian Canon or Liturgy of All Apostles.”

(also 7ANF 534).

* St Gregory was the “illuminator” of the Armenians with the Gospel of Jesus.

St. James was the LORD’s foster-brother (son to Joseph of Nazareth by a previous marriage), and was installed as the head of the Jerusalem Messianic Bet Din (later anachronistically called a “Council” – see Acts 11:1-18, and 15:6-33) at the behest of Jesus Himself by St Joseph of Arimathea.

St James also wrote the Canonical Epistle which bears his name (written 49CE at the same time as the Acts 15 gathering), which Epistle was meant to accompany the Jerusalem Decree of Acts 15:22-29.

I trust that this addresses the issue of the antiquity and apostolicity and authority of the doctrine of the Trinity.

JohnB